Federal Courts Exam on Travel Ban, Presidential Immunity, Etc.

by Michael Dorf

Once again, it's that time of year when I post an exam. There are three questions. As always, creative answers are welcome in the comments, but I won't grade them. I apologize for the fact that despite my best efforts to concoct outlandish hypothetical examples based on real events, the actual real events are still more outlandish.

-----------

The following facts should be assumed for question 1.

The legislative history, including the House Report,

the Senate Report, and statements on the floor of each chamber by the sponsors

and supporters of JIA indicate that Congress intended JIA to prevent a single

district court judge from issuing a nationwide injunction blocking enforcement

of President Trump’s March 6, 2017 (revised) Executive

Order Protecting The Nation From Foreign Terrorist

Entry Into The United States (“Revised Travel Ban”) against aliens from the six

countries subject to the order or any aliens seeking refugee status.

Once again, it's that time of year when I post an exam. There are three questions. As always, creative answers are welcome in the comments, but I won't grade them. I apologize for the fact that despite my best efforts to concoct outlandish hypothetical examples based on real events, the actual real events are still more outlandish.

-----------

The following facts should be assumed for question 1.

After “going nuclear” and abolishing

the filibuster for ordinary legislation, Congress passes and President Trump

signs the Jurisdiction Improvement Act (“JIA”). In pertinent part, it provides

as follows:

Notwithstanding any other provision of

law, no court of the United States shall have jurisdiction to issue a

nationwide injunction in any case challenging an executive order, on its face

or as applied, regarding entry of aliens into the country, unless the case has

been properly certified as a class action on behalf of a plaintiff class

consisting of all aliens who stand to benefit from the proposed nationwide

injunction.

The legislative history, including the House Report,

the Senate Report, and statements on the floor of each chamber by the sponsors

and supporters of JIA indicate that Congress intended JIA to prevent a single

district court judge from issuing a nationwide injunction blocking enforcement

of President Trump’s March 6, 2017 (revised) Executive

Order Protecting The Nation From Foreign Terrorist

Entry Into The United States (“Revised Travel Ban”) against aliens from the six

countries subject to the order or any aliens seeking refugee status.

As you know, several federal

district courts that have issued temporary restraining orders or preliminary

injunctions against the March 6 Executive Order and its predecessor have done so on a nationwide basis,

reasoning that complete relief could not otherwise be granted to the parties

(because people destined for, say, Seattle or Honolulu, might enter the country

in airports located throughout the country), and noting that the federal

government had not proposed a narrower injunction that would also provide the

parties with complete relief. Those rulings are working their way through the

U.S. courts of appeals and are expected to eventually arrive at the U.S.

Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, you have just been hired

as a law clerk to Justice Gorsuch. (Congratulations.) Because he did not

participate in oral argument in most of the cases currently on the Court’s

docket, Justice Gorsuch has some time on his hands and wants to use it to get

up to speed on the impending immigration case. He tells you that in the absence

of JIA, he would vote to affirm a district court order granting a nationwide

injunction against the Revised Travel Ban, because he thinks that the

plaintiffs have standing, have shown a likelihood of success on the merits of

their Establishment Clause claims, and cannot receive complete relief absent a

nationwide injunction. However, Justice Gorsuch also tells you that he does not

believe that a class action could be “properly

certified” within the meaning of JIA, because aliens outside the United States

without prior ties to this country would not themselves have standing to

file suit, and thus no class representative would be able to “fairly and

adequately protect the interests of the class.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a)(4). Complicating

the matter further, Justice Gorsuch is uncertain whether JIA, on its face or as

applied to the Revised Travel Ban, is constitutional.

Question

1: Write the analysis and conclusion portions of a memorandum to Justice

Gorsuch addressing the constitutionality of JIA given the views he reported to

you.

The following facts should be assumed

for question 2.

President Trump has long sought to

“open up” American libel law. In pursuit of that end, Congress passes and

President Trump signs the Make America Whole Act (“MAWA”). In pertinent part,

it provides:

Findings. The inability of public figures and

public officials to recover for defamation pursuant to New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) and its progeny harms the mental health of such persons

when they are defamed in the dishonest media.

Delegation. The Secretary of Health and Human

Services shall have authority to promulgate regulations that promote the mental

health of defamation victims by lowering the threshold for liability. That

authority includes the power to create private rights of action.

Immediately

following the enactment of MAWA, HHS begins a rulemaking. After notice and

comment, Secretary Price promulgates the following final rule:

1)

Any person who is defamed by any other person or entity in, or through the use

of the channels or instrumentalities of, or affecting interstate or foreign

commerce shall have a federal cause of action against such other person or

entity.

2)

The law to be applied in any such suit shall be federal common law. The content

of federal common law in such suit shall be the law of the most pro-plaintiff

jurisdiction in which the alleged defamatory statement was published or read,

including, where applicable, any foreign jurisdiction.

Shortly

after the promulgation of the foregoing rule, Hillary Clinton, a citizen of New

York, sues President Donald Trump, also a citizen of New York (because he does

not intend to reside in the White House indefinitely), in federal district

court in the SDNY, seeking damages for defamation under the HHS rule, based on

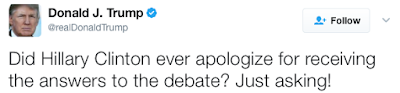

the following tweet of April 3, 2017:

The

tweet apparently refers to an incident during the 2016 presidential primary

season when Donna Brazile, who was interim chair of the Democratic National

Committee and a commentator for CNN, leaked questions for an upcoming town hall

to the Clinton campaign but not to the Sanders campaign. Clinton’s complaint

acknowledges that the leak occurred but contends that she did not “receiv[e]

the answers” to any questions, just some of the questions themselves. Her

complaint contends that the law of the United Kingdom—which is more favorable

to defamation plaintiffs than the law of any state in the U.S.—applies to her

claim per the terms of the HHS rule, in light of the fact that Trump has

thousands of Twitter followers in the U.K.

The

case is being litigated on behalf of Clinton by the law firm where, following your

clerkship with Justice Gorsuch, you are now an associate. The partner handling

the case informs you that President Trump has filed a motion to dismiss,

offering multiple grounds. She asks you not

to address the question whether the application of U.K. libel law would

violate the First Amendment, but to address the following three issues:

a)

Will Trump prevail on his motion to dismiss on the ground that he has immunity

pursuant to Nixon v. Fitzgerald, 457

U.S. 731 (1982)?

b)

Did HHS have the authority to create a private right of action via a

regulation?

c)

Is jurisdiction proper under 28 U.S.C. § 1331 or any other existing provision

of law?

Question

2: Write the analysis and conclusion portions of a memorandum to the

partner addressing the foregoing three questions and any other issues we

covered in class that may be relevant to the disposition of the case.

Question

3: Does the Suspension Clause limit the power of Congress to restrict the

availability of the writ of habeas corpus as a collateral remedy? If so, how?

If not, why not? Write your answer in the form of a dialogue in the style of

Henry M. Hart, Jr., The Power of Congress

to Limit the Jurisdiction of Federal Courts: An Exercise in Dialectic, 66

Harv. L. Rev. 1362 (1953), which was originally written for the first edition

of the Hart & Wechsler casebook and is excerpted in the Seventh edition,

which we used in class. Advice: Do not spend much if any of your time

(re-)reading Hart’s article. It should serve only as a style guide.