Public and Pundit Confusion Between Slowing Inflation and Promoting Deflation

Here on the blog yesterday I drew an analogy between popular confusion about fiscal policy (highlighting the frequent but misleading comparisons between household finance and public finance) and legal interpretation (describing the popular appeal of original-intent originalism as rooted in a misleading comparison to everyday speech). At the end of yesterday's essay, I suggested that there are likely other similar public misconceptions that work in roughly the same way. I gave as an example of one roughly analogous phenomenon the frequent claim that government or universities should be run like businesses.

Because I closed the blog to comments a while back in response to spammers and trolls, I didn't end yesterday's essay with a call for readers to provide additional examples but that didn't stop some intrepid readers from writing to me privately. One such reader offered public misunderstandings about inflation as an example. The particular misconception people hold about inflation is not exactly analogous to the misleading comparisons between household finance and public finance or to everyday speech and law. As I'll explain, people don't draw on experience with something like inflation in one domain and then misapply it to another. Nonetheless, the confusion about inflation is widespread and potentially quite dangerous as a matter of politics.

So what is the confusion? Simply that effective policy in combating inflation would lower prices. In fact, however, systematically lowering prices--deflation--is not and should not be the goal of monetary policy (via the Federal Reserve), fiscal policy (via Congress), or any other sort of public policy. Systematic deflation can be much more devastating to an economy than above-average inflation, rivaling hyper-inflation in its ill effects. According to my reader, many people who currently complain about inflation are confusing decreases in inflation with price deflation.

That seems plausible. After all, inflation currently hovers around 3.2 percent, which is higher than the Fed's target of 2 percent but arguably a better target for the economy's overall health. So if people are still grumbling about inflation, that could be because they want to see prices going down, not just climbing more slowly than before.

But wait. Are people actually confused about what it means to lower inflation? I haven't conducted a survey, so I can't say for sure, but I can provide a supportive anecdote in the form of my analysis of a guest opinion essay in yesterday's NY Times by Karen Petrou, who writes frequently about economic policy. I'll get to the confusion after a detour into a related question that frames her essay.

Petrou aims to explain why polling data show that voters in swing states are not giving President Biden credit for "Bidenomics," which, together with the Fed's monetary policy, seems to have managed to bring down inflation without sparking the recession that most economists were predicting as recently as a year ago--nailing the elusive "soft landing." Petrou's main argument is that in a country like ours, with substantial economic inequality, positive aggregate and average data can disguise negative effects for a great many people.

To give my own supportive hypothetical schematic example, suppose there are 100 people in an economy and inflation is running at 3 percent per year, 99 people in the economy have flat incomes, but the one extraordinarily rich person--who is wealthier than everyone else combined--sees his own income double in under a year. The mean income would more than keep pace with inflation, but 99 percent of the population would see their purchasing power shrink by the rate of inflation.

Is that analogous to what's actually happening? To some extent, perhaps, but economic statistics typically do not simply focus on aggregates and means; they also provide information about medians and percentile effects. When the headline says "wage growth outpaces inflation," the story will likely focus on wage growth for typical or hourly workers, not on average wages as distorted by distribution effects.

To be clear, I agree with Petrou that the distribution of wealth and income in the United States is highly problematic. I'm just not persuaded that economic inequality accounts for (or entirely accounts for) voters' failure to give Biden more credit for the economy.

What does account for it? Part of the answer is political polarization. Republicans perceive the economy as worse under a Democratic president than under a Republican one (and vice-versa), regardless of the actual state of the economy or even the actual state of their own households. So any president's economic poll numbers will be lower than one might otherwise expect in good economic times.

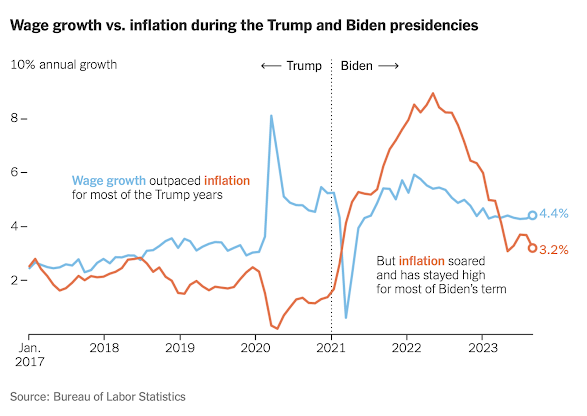

That said, Petrou is correct that even Democratic voters and independents seem to be giving President Biden overall poor marks for the economy, despite what the White House touts as decent economic data. As I said, some of that could be a distributional effect. But I also suspect other forces at work. We can get a handle on some of them by examining the following graph that was included in Petrou's essay.

I don't know whether Petrou or the Times editors captioned the graph, but whoever did it wasn't paying much attention to what the data actually show. That second caption says "inflation soared and has stayed high for most of Biden's term." It did in fact soar, but anyone with eyes can see that while inflation hasn't back come down to the artificial low of near-zero at the height of the pandemic, inflation has come down to an arguably healthy rate nearly as quickly as it rose.

So how do we explain the fact that voters tell pollsters that the economy is worse than it was a year ago, when that last year corresponded with the precipitous decline in inflation? I would point to two related factors.

First, as the graph above shows, wage growth has only begun to outpace inflation in the last six months or so, and then only by about 1 percent. That's too recent and too small a change for people to have noticed a substantial increase in purchasing power.

Second, and relatedly, at least when people are not feeling a substantial increase in purchasing power, they are likely to labor under the confusion I used to introduce this topic: because the Fed has brought down inflation but not prices, people continue to experience prices as quite high and have the unrealistic expectation that effective government policy would not simply slow the increase in prices but actually make goods and services cheaper. When they say, seemingly paradoxically, that the economy is worse off than it was a year ago, they are probably not calibrating exactly to 365 days earlier but simply thinking about how high prices are now compared with where prices stood two or three years ago. And because inflation is still positive, prices are in fact even higher than they were a year ago.

Petrou herself seems to labor under the confusion between slowing inflation (the goal of government policy when inflation is high) and actually aiming at deflation (a terrible idea). In explaining the seeming disconnect between the overall economy and public perception, she writes that

Bidenomics has failed to create sufficient tangible improvement in the lives of most voters in a world in which groceries still cost more than they did a year ago, average rent and mortgage rates have spiked and health and child care grow ever more unaffordable.

That's a mixture of sense and nonsense. Mortgage rates are a real source of economic pain for people looking to purchase homes or paying adjustable rates on existing mortgages. Health insurance inflation is up too, but as recently as June the inflation rate of health care was lower than overall inflation. In any event, let's focus on the whopper of a blunder in that sentence: "groceries still cost more than they did a year ago." Well, yes, of course they do. Even in a low-but-nonzero-inflation environment, goods and services as a whole will cost more than they did a year ago. If they didn't, we would be experiencing harmful deflation.

At this point, I could concede that food (and energy) prices tend to be more volatile than prices of items that are the focus of so-called "core" inflation; thus, a one-year decline in food prices would not necessarily signal unhealthy deflation throughout the economy. But it's clear that by lumping food prices in with other kinds of economic data, Petrou was not making a claim about food price volatility. She was simply saying that it's understandable for people to feel bad about the economy because the price of something is still higher than it was a year ago. Far from identifying a misunderstanding in others, she was pretty clearly exhibiting it herself.

In my essay yesterday, I said that the appeal of misleading analogies involving public finance and legal interpretation was common not only among the general public but also among politicians and pundits. The same appears to be true for at least one pundit opining prominently about inflation. I leave as an exercise for the reader the identification of other pundits who labor under the confusion discussed here--between bringing down the rate of inflation and bringing down prices.