by Matthew Tokson

A lawsuit recently filed in federal court alleges that Connecticut environmental enforcement officers strapped a camera around the neck of a bear who was known to frequent the plaintiffs’ property. The officers hoped to obtain evidence that the property owners, Mark and Carol Brault, were violating a local law against feeding wild bears. The camera-wearing bear traveled to within 200 yards of the Braults' residence, transmitting images of their property to the officers. The Braults assert that this violated their Fourth Amendment rights.

In addition to being ripe for puns, the case raises several interesting Fourth Amendment and property law issues. Bear with me as I explore the complex questions raised by this unusual scenario.

The Connecticut officials and their furry associate may have violated the Braults' Fourth Amendment rights in one of two ways. First, they might have violated the "trespass test" by physically encroaching on the Braults' property for investigative purposes. Second, they may have violated the Braults'

reasonable expectation of privacy by photographing their yard without a warrant.

A key issue in this case is whether the bear entered the Braults' yard or merely their open fields. The Fourth Amendment provides dramatically different levels of protection for the "curtilage" of a home, i.e. the yard area immediately surrounding a residence, and the fields or wilderness that otherwise constitute the owner's property. The Supreme Court

has held that the Fourth Amendment does not apply to open fields at all. By contrast, the curtilage of a house

is protected almost as carefully as the house itself.

Here, it's unlikely that the bear actually entered the curtilage of the Braults' residence. The Court has laid out a four-factor test for curtilage, looking at the proximity of the area to the home, whether the area is enclosed by a fence along with the home, the nature of the uses to which the area is put, and any steps taken by the resident to protect the area from observation. While it's not clear exactly where the bear went or what uses the Braults made of that area, the fact that the bear was roughly 200 yards away from their house suggests that they did not enter into the Braults' yard. The Supreme Court

has found that land 60 yards away from a house was not curtilage, for example. If the bear only entered the Braults' open fields, then there was no violation of the Fourth Amendment's trespass test. Likewise, the

Court has held that gathering information about a person's open fields does not violate their reasonable expectation of privacy.

But what if the bear did enter the curtilage of the Braults' home, or at least photographed the curtilage from where they prowled? It's a novel question, but it's at least possible that the bear incursion could be considered a Fourth Amendment violation under the trespass test, and under the reasonable expectation of privacy test as well.

The Supreme Court

has held that the police violated the Fourth Amendment when they walked up to a suspect's house with a drug-sniffing dog for the purposes of detecting drugs. The same holding would likely have obtained even if the police officers had remained just outside of the property while sending the dog onto it and observing the dog's reactions. Strapping a camera to a bear with the intent that they go on a suspect's curtilage and reveal information is likely the same type of physical intrusion on protected property that was ruled unconstitutional in

Florida v. Jardines. To be sure, courts addressing situations where trained dogs either enter a car or detect drugs without police prompting usually find that such actions do not trigger the Fourth Amendment. But those cases are likely distinguishable, because they involve no intentional police investigative action. They turn on the fact that the officers did not "

have as [their] purpose a desire to find something or obtain information." But here, the officers plainly did have the purpose of obtaining information from the camera they placed, no doubt very carefully, around the bear's neck. They caused a government information-gathering device to enter the Braults' curtilage (I'm assuming here), and in doing so they violated the Braults' Fourth Amendment rights just as the officers in

Jardines did by bringing a drug-sniffing dog into a homeowner's front yard. Perhaps the officers could convincingly argue that they only intended that the bear enter the Braults' open fields and not their curtilage, and that the bear's incursion into the yard was unintentional. This may be chopping things a bit too finely, and rewarding the officers for a negligent intrusion of surveillance equipment onto protected property. But so long as the officers did not intend to encroach on protected property for the purpose of gathering information, they may not be responsible for the overzealousness of their ursine agent.

In any event, it's unlikely that the bear actually did enter the Braults' curtilage. Perhaps a more relevant question is whether placing a camera on an animal and observing the Braults' yard violated their reasonable expectation of privacy. This general issue has not come up in the Supreme Court cases involving open fields, largely because the police in those cases didn't observe anything incriminating in the curtilage. In most cases, even those involving large properties, the curtilage could easily be observed by anyone approaching the house, and therefore its mere appearance would not be private. Here, per a map of the area, the Braults' house is likely visible (and accessible) from a public road, and their curtilage would accordingly not be considered private or protected from view. In the unlikely event that their yard is both invisible from public areas and not accessible to the public--they did apparently put up several "No Trespassing" signs around some portions of their property--then they might have a Fourth Amendment right against video surveillance of their otherwise hidden yard.

In

several cases, government agents setting up surveillance cameras capable of observing parts of a suspect's yard that were obscured from public view have violated the suspect's reasonable expectations of privacy. Typically, these cases involve cameras that peer over a person's opaque fence to see parts of their yard not visible from the street. But similar principles may apply to a curtilage that is so remote from any public area as not to be visible to anyone but intruders, or

that is only visible from private property. If the government used a camera (and a bear) to observe curtilage that was otherwise invisible to the public, it likely violated the target's reasonable expectation of privacy.

There is also the possibility that a court might conclude exposure to animals itself eliminates any Fourth Amendment right to privacy in a given parcel of private land. In

California v. Greenwood, the Supreme Court held that trash placed on a curb was deemed exposed to the public, in part because "plastic garbage bags left on or at the side of a public street are readily accessible to animals, children, scavengers, snoops, and other members of the public." It's possible that the bear might be considered a Fourth-Amendment-relevant observer who frequents the Brault's curtilage, rendering it non-private. However, it's more likely that the Court had in mind raccoons strewing trash for all to see or, as in

one case cited by the Court, dogs dragging trash bags off the property, rather than animals actually observing the trash themselves.

What can we learn from all of this? First, the open fields doctrine permits all manner of investigative intrusions on non-residential real property, from

placing cameras on a person's land to mounting them on the local wildlife. Second, the Fourth Amendment's trespass test is complex and often confusing. I didn't even delve into the common law doctrine stating that wild animals become one's property when they wander onto one's land. That's not especially relevant, because the "trespass test" doesn't actually concern itself with trespass law per se; rather, it's more of a "physical touching for information gathering purposes" test. Third, there's at least some limit to what the government can lawfully observe with a camera, especially if some or all of a person's property is not visible to the public. And finally, it turns out that bears are pretty predictable creatures, and you can probably anticipate where they'll go, if you know them well enough.

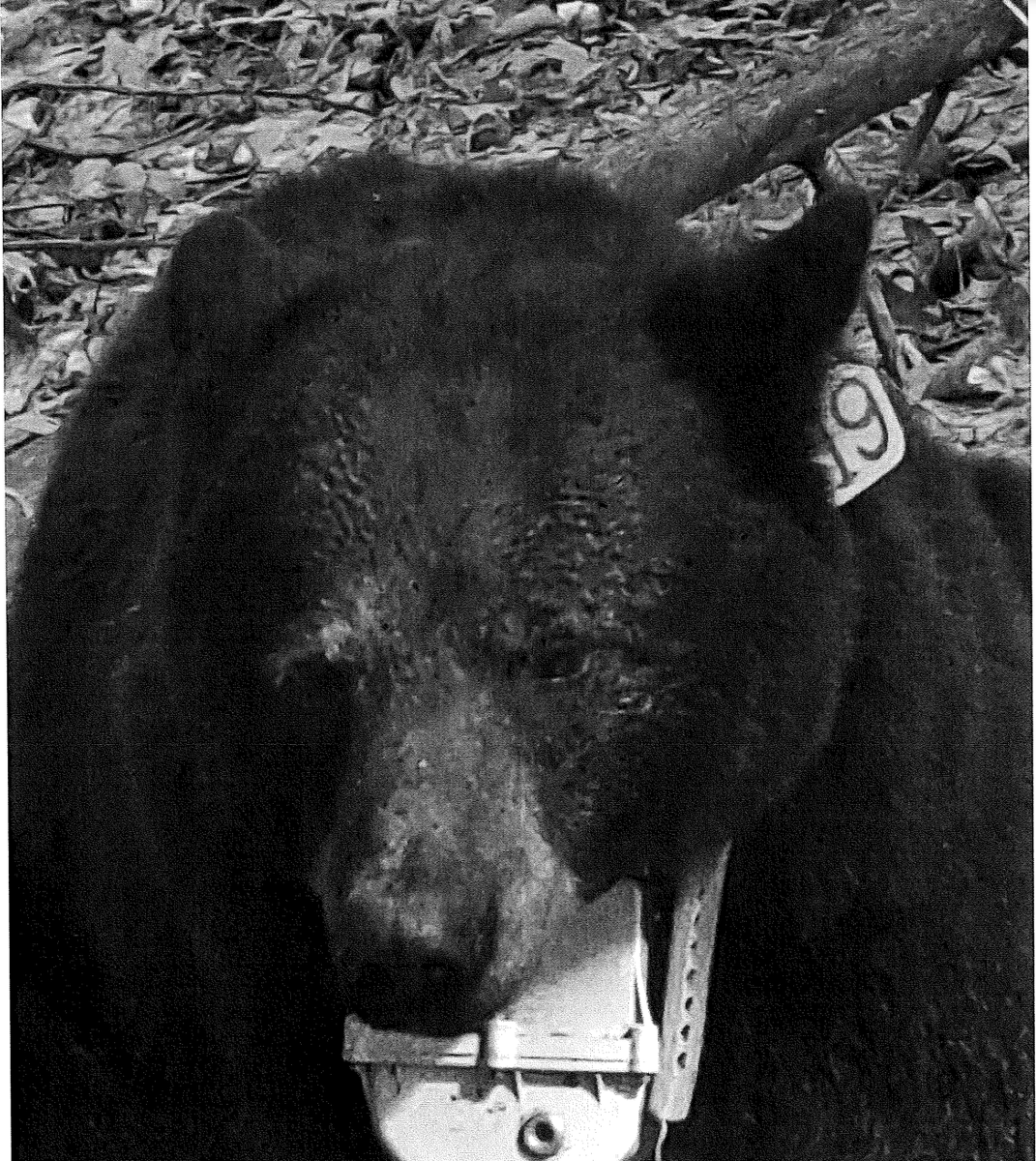

Or perhaps this bear is just really committed to catching lawbreakers no matter how minor the infraction. Behold the face of modern surveillance:

Don't even think of starting a forest fire on this bear's watch.